Text as in RASA Indian Performing Arts in the Last Twenty-five Years Vol.1. ed: Sunil Kothari, Anamika Kala Sangam PublicaCons, Calcu0a. 1995. Revisited in 2025.

India has been the historic melting pot of centuries yet, forty-six years after Independence, the Golden Age of Sanskritism still dominated cultural expression, in theory, if not always in actual practice. Dancers staged claims to a mythic past but through twentieth century sensibilities. Songs of intimate devotion were and are performed on huge proscenium stages, traditionally designed for separation not intimacy. Audiences clap after performances. This formal response is but one mark of the lingering effects of Anglo-Euro-American culture. But, the indelible imprints of present and recent histories of colonization are denied even as they persist.

This article was written retrospectively in the 90s about dancing in the 1970s and 80s. It is about my works introducing modern dance in India, when modern dance was still modern. I sought to acknowledge the intercultural realities of our daily lives, constantly in evidence but ignored in cultural expression. I sought to place their significance in a value system that becomes defined as choices are made in response to changing circumstances. The splits and gaps between past ideologies and present realities, words and actions, concepts and direct personal experience (pratyaksha) are at the base of my choreography. These unconfronted unacknowledged splits need attention or wounds (sanskaras) of colonialism, fundamentalism, all 'isms,' will never heal.

I dance to heal the disparate conflicts between the cultures that most deeply touch my existence.

Truth is ever on the margin between the established past and the challenging future.

Reality is the razor's edge between cultural properties.

Truth is a bottomless hole.

Realizations flash in an instant and go unseen.

My dance is my Reality.

My work and life is liminal (1).

Perhaps it does not matter what "Art" is. Whose "Art" is meant by that word anyway?

My work is interculturally interactive. It has been informed by several vocabularies. In the chronological order in which I studied and performed individually and collectively these vocabularies, they are Hatha yoga, Indian sculpture (2), classical ballet, bharatanatyam, the Graham, Cunningham, Horton/Ailey techniques and other modern and post-modern dances(3).

Scholar, Indophile and Rasika, Joan Erdman finds my work "programmatic"(4) She explained that the choreography as well as the links between movements are rule generated. Indeed, my struggle is to integrate the disparate vocabularies, influences and experiences in my life, into a structural integrity in the layers of my choreography. This ‘works’ only when I deeply honor what feels ‘right.’ There are unspoken rules in the grammars of most culturally inflected dance forms.

Many of the movements and dances I create can be found in the rules in NatyaShastra. It is out of sheer necessity that I point this out to those who refuse to see. That I would actually stake such a claim is an acknowledgement of the value that is given to sanskritization in our culture. Equally do I honour deeply intimate experiences of the sheer joy of physicality, of the intoxication of the pleasures of my body, when it is well tuned (5). My research started very simply when Ananda Shankar presented me in 1970 a tape of some music he had just recorded. The integration of the sounds of a Moog synthesizer and sitar, the tonalities of north Indian music and western melodic structures inspired me. I began to experiment with indulging in exactly those kinds of fluid movement dynamics that my body wanted to express but which were the antithesis of the intense often violent movement that I was then performing as a member of Pearl Lang's dance company. Images of the yakshi-s at Sanchi, where I had visited as a teenager spontaneously entered the work. The dance was to be an exploration of the lyrical quality lasya, and this was what it was first named. Later an expanded version of this choreography became a staple work in the repertory of the dance company of my friend Tina Yuan of the Alvin Ailey company during their tour of Taiwan and Los Angeles in 1974.

In a festival of dances at Bryant Park, New York in 1971 the early solo version of Yakshi was noticed: "an" interesting piece to sitar and synthesizer, combining her country's classical dance style with the far-more-body-conscious techniques of American modern.”(6) These two little but loaded lines set me up for two years of performances with a dance company that travelled across the East Coast of the United States, Canada, the Caribbean Islands and some of the best theatres in New York.

In 1973 when the United States Information Service (USIS) invited me to present a series of lecture-demonstrations across India, people thought 'modern dance' meant the rhumba, tango and waltz. When I tried to explain before the performances that my work was intercultural people said 'How can that be? East is East and West is ... ? At best they expected some kind of filmi exotica.

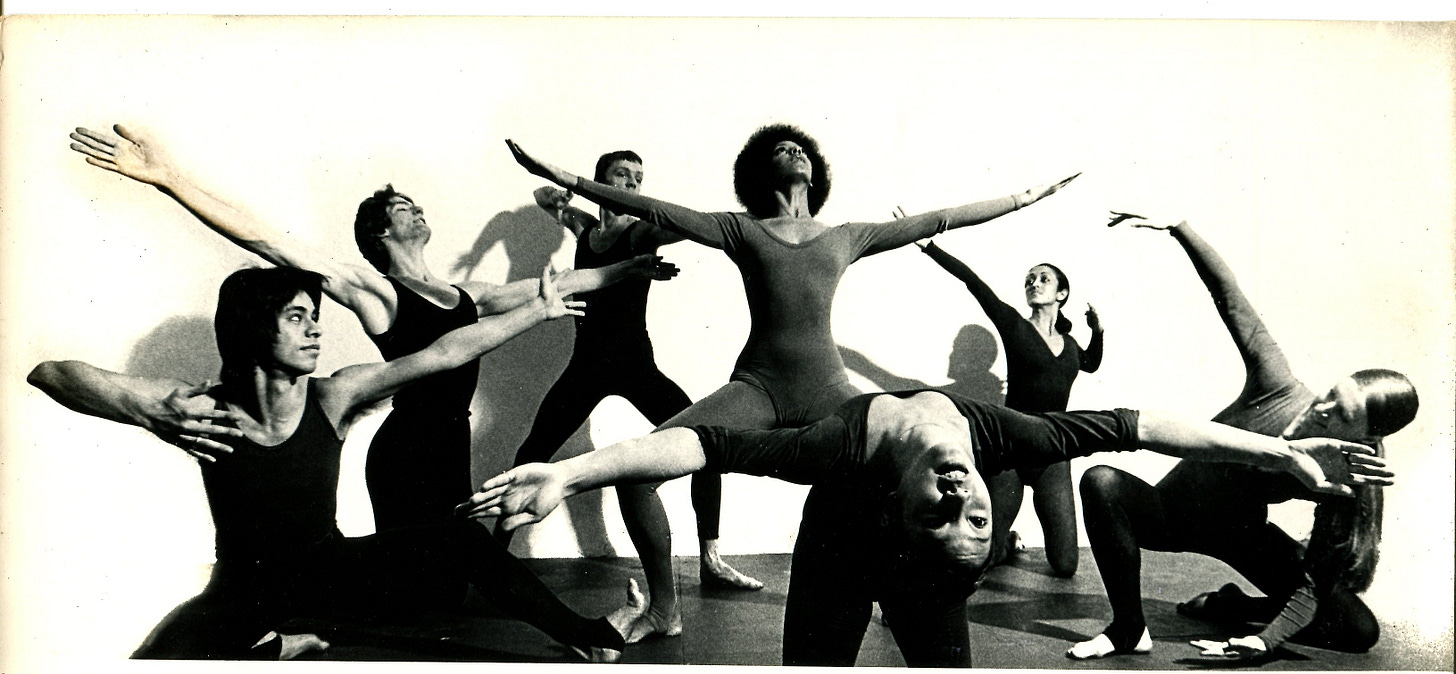

After the performances in 1973 and 1974, audience reactions were surprised and excited(7). Bewilderment and enthusiasm surrounded all our performances on this tour and the next tour which included my company The Mandala Dance Theatre consisting of eight dancers from New York including guest artist Yuriko.

News reports either noted or attempted to clarify prevailing confusions(8). The responses, especially of college students, seemed to suggest that they shared my need to integrate the disparate elements of our culture in our time and make accessible the heritage of the past.

Yaksha-Yakshi (1974) was described as an'outstanding dance which captures the entire spectrum of the Indian classical dance ethos.'(9) In March 1974, said a Bombay newspaper, “An Indian girl made dance history recently. She launched contemporary dance on the stage in India. It held her audience spellbound... “(10)

A succession of similar explorations followed. Rangilo/Exercise 1 (1978) experimented for example with transforming symmetrical shapes from one vocabulary into its nearest corresponding symmetrical shape in another vocabulary (11).

Several works that explored abstract choreographic relationships followed between 1974-1982. Asana, in slow motion emphasized the fluidity of Hatha yoga asana to the accompaniment of the Devi Stotram (12). Though the choreography for the opera Lakme, was based upon my modern dance and Bharata Natyam training, it had to be taught to classically trained ballet dancers in France, who brought another dimension of interculturality into their performance (13).

In The Solkattu Game, commissioned by the Dance Theatre of Harlem in 1987 the movement patterns follow the solkattu structures, but many of the movements were inspired by the moods and tensions of the dancers and by their kinetic responses to Bharata Natyam. Also in the genre of abstract explorations relating contemporary and Indian 'classical' dance is the post-minimal Sixakam choreographed for six young dancers in Bombay and commissioned by the Bombay Arts Festival 1987 (14).

In 1989 and 1993 I had the opportunity to restage a dance entitled Shringara -A Piece for You and Three Dancers. The music specially composed by Nicolas Naylor-Leyland involved instruments and stylistic elements from various cultures that co-exist in very close proximity in New York city. The music included Radha Thomas's sensuous voice scatting in Carnatic style which provided a very special flavour. The choreography enabled each individual dancer the opportunity to participate creatively in developing her role, while the unity of the concept and close co-ordination of activities was still maintained. In the recent performance at the opening of the 21st Annual Conference on South Asia at Madison, Wisconsin, Parul Shah created the role of the Bharatanatyam dancer, and Purnima Shah played the Kathak dancer. The program notes explained that the dance was dedicated to the first generation of South Asian young adults born and growing up in the United States between cultures. As teen-agers they are torn between conflicting value systems. 'To date or not to date' is their intense problem because the customs and social values of their parents were so opposed to what was happening in their American environment. In the dance, three viewpoints about Shringara are juxtaposed or presented sequentially, and the question posed, "Which shringara (inner erotic sentiment) does one choose ? Is there a choice ?" (15).

Often a strong emotional experience has triggered the choreography of a dance. In these situations, the music and the movements have been abstract, but were chosen for their sympathy with the experience I wished to project. Whispers (1975 ) recalls the setting sun. Puri Night (1974) recalls the phosphorescent foam of the ocean on a moonlit night on the beach at Puri where space and time expanded into the inexpressible.

Incredible

Puri

Night

Spirit

Seduction

fear

A new day

The music for this dance was Raga Chandrakauns played on the rudra vina by Zia Muhiyuddin Dagar and it was included in the repertory of my 1978 performances in India as was Amrit.

Amrit was about the simultaneous experience of extremes of emotion. It was composed as I was getting ready to leave New York 'for good' in 1977, and returning to India. The excitement of the direction I had chosen and the pull of more recent ties wrenched in opposite directions, and in between I discovered - a rainbow (17).

In 1980 I became involved with exploring narrative. The simple groundwork had already been laid with my choreography of Roberta Flack's The First Time choreographed and performed in India in 1978 as a kind of padam. My friend Nada Clyne composed a set of three songs in the style of American folk ballads and based on her inner experiences while she stayed in an ashram at Ganeshpuri . Clyne accompanied herself with an autoharp and also participated in the choreographic and interpretative process.

The dance is already described in my earlier article where I wrote : 'These dances sustained me inwardly and as repertory. Something in the act of performing them seemed to lead me closer to emotions and energies deep inside and beyond my comprehension. My relationship to these dances changed when Baba passed away in 1982'(18). I no longer perform these dances.

Some questioned my inclusion of hasta-s for the narrative sections and adavus in the nritta (abstract dance) sections. Yet, often, recent post-modern works cite clearly identifiable movements from the works of earlier choreographers and without controversy! Being born and brought up in India, I wondered why I should not incorporate in my own work the time-tested means of strengthening the mind and deepening experience that Bharata Natyam dancers have available to them (19).

“Angikam bhuvanam yasya vachikam” goes the dhyana shloka in Sanskrit. .. At the Music Academy (Aug 23) I watch a totally different interpretation of this. The idiom is unimaginable - the Martha Graham technique of modern dance! The song is in English but the expression is of an abstract Indian philosophical idea. The precision of her style becomes a kind of moving diagram (yantra) The dancer has communicated. I recognize 'angikam ... Her body is western with years of training in various modern dance techniques. The movements are precise and ruthlessly professional but somehow Indianness shows through”(21).

My next few narrative and emotional dances have no sung texts. Hasta-s are extensively utilized in a section of Winds of Shiva entitled 'Birth of the Stars', where 'a modern-dance attack and physicality' were 'smoothly blended' with the hasta mudra(22). To those unfamiliar with the detailed meanings of the hasta, the dance was still accessible (23).

Working in dual sensibilities and vocabularies is as full of possibilities as it is limiting. Each culture and each dance vocabulary has its taboos and its hallowed criteria. Working interculturally involves many frames of reference. It can make people uncomfortable because their frames of reference are higgledy piggledized Alternatively, intercultural dances can stimulate new realizations, new possibilities. I have had my share of both aspects of this process.

In intercultural performances, what is familiar to the viewer is taken for granted, is transparent. The other less familiar elements of the same dance are always opaque, identifiable. The space between the taken-for-granted/transparent movements and the opaque/different movements reflects the split between what is intended and what is expected. In each of the countries where I performed, local critics, impresarios and dance educators would expect the performance to conform to their concepts of what 'Contemporary Indian dance' should be. If the dance is to communicate, it should succeed on their terms. Yet if the choreographer were to adopt different criteria for performing the same dance in different countries, then what would happen to the integrity of the dance and its cultural moorings?(24)

On the other side are those avant garde events that do indeed affirm and celebrate complexities. Many provocative arguments and discussions arose at an international festival of solo performances by nine women in experimental theater in which I participated in January 1987. The event was held appropriately enough at The Double Edge Theater in Boston. The festival title Electra had 'something to do with independence and rebellion. We did not want somebody who was clear. We wanted someone who was complex and made her own choices '(25).

Winds of Shiva (1984 ) is a multilayered personal representation of Creation cosmologies. The narrative, as originally conceived by Igor Wakhevitch was based on physical theories. As we worked together, a cosmological perspective gradually leaked into the dance until it permeated throughout and replaced the earlier more 'scientific' imagery.

Co-incidentally, the cover of the program for The East-West Encounter where this was first featured shows lines of force superimposed upon the classic icon of Shiva Nataraja (the Dancer.) representing a Capraesque merging of Indian cosmology and quantum physics.

Winds of Shiva is not about Hinduism, an Oriental perception of it, or about religiosity, though recent Hindu fundamentalists had claimed it as serving their ends (26). Dance critic Shanta Serbjeet Singh (and others later) associated the dance with the Rig Vedic hymns imbued with wonder at the awesomeness of the forces of nature and the universe(27). The play of light and dark in 'Meditation' reflects my ongoing involvement with the oppositions inherent in Zarathushtrianism(28). The music for the same section is reminiscent of the tonalities of music associated with the ashram in Pondicherry where the composer, Igor Wakhevitch now resides. Permeating through all these layerings of associations, are those of our individual creative processes.

In terms of percentages of perspiration to inspiration, I gratefully acknowledge that the choreography for Draupadi's Saree (1980;) was not mine. It was a gift. I literally 'saw' the dance with my eyes closed, and even as I reconstructed what I had seen, I was not conscious of its truths till critics told me what they were (29). Deep Inside (1980) and Asana similarly have also been mysterious gifts.

“In Deep Inside her sitting postures with flexion of the legs were superb, reminiscent of Karana-s of Chidambaram. She is poised at a moment from where her flights in to creativity are just exquisite “(30).

The artisans of India's ancient arts perceived their work as a process of giving form to forces beyond themselves. Fascinated, I wondered if it was possible to make this connection and re-birth a dance at each performance. I set myself the dangerous task of seeking publicly this unpredictable and very special connection anew with each performance of 'Meditating.'

In this dance, improvisation is an essential ingredient. The other component consists of the now internalized rules for manipulating adavu in space and time, and incorporating movements from my multi-lingual vocabulary of movement with the spatial environment of this dance. Beautiful multidimensional geometric projections of light covered the entire stage, my moving body and the background.

Performing this work demands intense multi-focused attention on minute details of movements and on the everchanging musical, emotional and spatial environments in which this dance is performed. By deliberately choosing a very open structure for this dance as opposed to set sequences of movement, I hoped that a kind of truth, a sensitivity to each time and place would emerge. While each performance of 'Meditating' reflects a performer's own internal baggage at that time, I have learned that each event is also a unique result of its time, place, sponsor and audience.

India was my home and source of inspiration. Yet, here, I never had access to a dance studio with adequate floors except for eighteen months while I was a Bhabha Fellow. How can a dancer perform without rehearsing ?

For my work, like most dancers whose dance involves any elevation, I needed sprung floors. Lack of it affects choreography and the ability to jump. The arrangements that preceded performances were nightmares, in spite of paying qualified light and sound technicians and in spite of negotiating rehearsal schedules months and weeks in advance with theatre personnel. In a very prestigious theatre in then Bombay, where my show was to complete a festival, a limited time slot had been allotted. When all the technical crew and rented lighting equipment arrived as scheduled, a film was being projected in the theatre, with three persons watching! And for these three individuals and the theatre manager’s scheduling snaffu, the entire rehersal with several dancers and tech crew had to be scrapped! Aah the maze of bureaucracy, patriarchies and social perceptions that envelope the dancing body!

In other countries there seems to be more respect and understanding of what needs to be accomplished to support a performance. For example, in Japan, I had sent my own hand drawn sketch of light arrangements in advance. To my dismay they had allotted an exceptionally short rehearsal timing. Yet despite the language problems, my rehearsal ended before schedule, for the lights and musical acoustics were to my total satisfaction. For twenty-five years, whenever I have been in India I have worked in difficult circumstances, on hard rehearsal floors, and hard stages. Now fifty percent of the cartilage has been removed from one knee whose anterior cruciate ligament is also severely damaged. The cartilage in the other knee is also torn. Still I dance.

Looking back at the choreographic developments over the last twenty-five years in India, much has changed. I notice that artists of the 'pure' and ‘classical’ forms are now experimenting with 'fusions' of dual or even multiple vocabularies. The use of hatha yoga asana and slow-motion adavu as I performed them at the East-West Dance Encounter in 1984, have been also explored with great effect by no less than Chandralekha, who brings her own special perceptions and innovations to the field. Jazz and ballet trained dancers in Bombay are curious about liaising Bharatanatyam. The music for my first dance Yakshi (1970), was electronic fusion music, and Wakhevitch's electronic music for Winds of Shiva (1984) preceded the New Age movement. Subsequently many innovative choreographers have included electronic elements in their music scores.

When I introduced the use of side-lighting in India in 1967 at a performance in the Vallabhai Patel stadium on Christmas eve, the producers and technicians thought it all very strange. At this same performance, Astad Deboo was one of eighteen dancers who were selected by audition to dance in my first commissioned modern work in India. Bharat Sharma attended one of my workshops on modern dance in 1978, and was motivated enough to get from me letters of introduction to Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival, and the Asian Cultural Council. His dedication and talent stood us proud in both events. From my many workshops sponsored by different cultural bodies and universities in India, I have friends in the dance field, whose ongoing commitment to independent work is important to me. My only regret is that there is not more community among dancers, and that minority expressions are devalued.

Once upon a time, I longed for dance guru. Someone who would take all responsibility for my perfect evolution as an artist; who would hand me a readymade repertory of dances, each one a glowing jewel. But this was not to be. I had to create for myself the dances I wanted to dance. As I keep dancing, each dance reflects changes in perceptions. The list is long of the many artistes, gurus and rasika-s, who have inspired me with their love of their dance.

An article like this would be incomplete if I did not acknowledge my debt to the one who opened the door of discovery to the creativity and strength inside myself, Baba Muktananda and to her who supports the continuance of the processes, Gurumayi.

I dance for love.

Love cannot be performed.

Love cannot be switched on and off.

Love is or is not there.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1. 'Liminal' as in between categories.

2. At St. Xavier's College, Bombay, I was awarded the Heras Memorial Award for my interest in Ancient Indian art history.

3. Since 1970 I have performed publicly, in dances choreographed by Alvin Ailey, Talley Beatty, Major Burchfield, Carmen DeLavallade, Louis Johnson, Shree Mohanrao Kallianpurkar, Pearl Lan,Sun Ock Lee, Daniel Maloney, Yvonne Rainer, Mrinalini Sarabhai, Padma Subrahmanyam, Anna Sokolow, Kei Takei, Yuriko and others.

4. Personal communication, Chicago, November 9, 1992.

5. See Comments on Body in interview with Mandakini Trivedi. The Sunday Times of lndia, Jan 17, 1992.

6. Robb Baker : "Liberated Dance : Out of the Concert Hall and into the Streets" Dance Magazine [New York Spring 1970].

7. For example, during our lecture demonstration at the National School of Drama in New Delhi, there was a power failure. The students simply would not accept that the event should be brought to a close. In the sCfling heat of a small overpacked unvenClated auditorium my partner Major H. Burchfield and I carried on at their insistence by the light of a gas lamp and with no sound!

8. Wohl, Elizabeth and Frank, "Dance for The New India." Span, [U.S.I.S.]July 1972. Dhyaneshwar Nadkarni. The Financial Express, March 3, 1974. Geeta Doctor, "Interpreta[ons" Parsiana Feb.-Mar. 1974. pp.33-35. Kothari, Sunil. "Where the Body Speaks." Evening News of lndia 22 Mar. 1975. Jam-e-Jamshed Bombay 12 March 1982. and others.

9. Shanta Serbjeet Singh : "A Symbol of Beauty." Hindustan Times 8 March 1974.

Karaka, Ratan, "Indian Girl Makes Dance History." The Current. March 16, 1974.

This and other dances in the repertory of U0ara Dances have been described in : Uttara Coorlawala : "In Search of A Meeting Place of East and West Through Dance "NCPA Quarterly Journal Vol. XII. No. 2. lBombay : NaConal Centre for Performing Arts 1984] Also Uttara Coorlawala "A Homi Bhabha Fellowship Report. 1986 Unpublished document in the archives of the Ford Foundation, New Delhi and the National Center for Performing arts, Bombay.

World Premiere at Le Grand Theatre du Tours, France. May 6, 1980.

February 27-March 1, 1981 at Le Grand Theatre de Tours, France.

The cast included Dodo Bhujwala, Shaimak Davar, Glen D'Mello, Neesha Jhaveri, Yasmin Stafford, Karla Singh, Vikram Kapadia and Sita Mani (alternate). The venue was The Nehru Auditorium, Nov 22, 1987.

Program of performance at Mitchell Theatre, University of Madison-Wisconsin, November 6, 1992. The program was co-sponsored by South Asian Area Center, the Dance Program, the Asian-American Studies Program and the Asian/Experimental Theatre Programs.

Program note from a performance in Vidyamandir Auditorium, Calcu0a, Dec 13, 1977. Sponsored by the United States InformaCon Service, Calcu0a.

The music of the dance Amrit was composed for me by Stanley B. Sussman, conductor and composer with the Martha Graham Company, Nureyev and Friends, The Cleveland Symphony ballet and other modern dance groups. He also a0ended some rehearsals and made suggestions about the movement that were incorporated.

Uttara Coorlawala "In Search of A MeeCng Place." Journal of the NaConal Centre for Performing Arts, Bombay, 1984.

ibid. p. 48.

It seems necessary to point out here, that though I have had intensive training in and am qualified to teach Graham-based technique, the choreography being described did not in anyway involve this style or vocabulary of dance.

V. R. Devika "Only I Am" Indian Express [Madras] 3 Sep. 1983.

Jennifer Dunning. "Asian Choreography in Two SensibiliCes." New York Times, 6 Dec. 1988

Doris Diether most clearly arCculated this aspect of the work in her review, "Array of Asian Dance at NYU Event." in The Villager 8 Dec. 1988. The following dance criCcs also appreciated this aspect of 'The Birth of The Stars.' J. L. Conklin. 'MulCmedia Effort at Peabody Displays Imagination, Craft.' The Sun [BalCmore Maryland] 31 Mar. 1988; Jennifer Dunning. 'Asian

Choreography in 2 Sensibilities.' New York Times, 6 Dec. 1988.

This view was expressed by Sarah Rubrige a BriCsh criCc speaking on contemporary Indian dances in London (specifically referring to the work of Shobhana Jeyasingha) at the recent joint conference of The Society of Dance History Scholars and The Congress on Research on Dance in New York City June 11-13, 1993.

Patti Hartigan, 'Staging a Rebellion' The Boston Globe, January 7, 1988.

Venkat Reddy, then editor for News India a weekly newspaper for Indians in North America expressed this view in 1991.

Dance critic Shanta Serbjeet Singh made this comment to Wakhevitch and Coorlawala personally aNer the first performance in January 1984.

Zarathustrianism is an ancient religion, usually described as the first to preach monotheism and the pursuit of truth. In this pursuit of truth the pious Zarathushtrian is constantly expected to seek and choose alignment with the forces of Righteousness (Asha, the Rig Vedic Rta) and light in the struggle against the negative forces of darkness.

This took place in the Siddha Yoga ashram in Miami, Fla, at a Cme when I was unable to accept an invitaCon to dance for my guru Swami Muktananda Paramahamsa, who was then in Los Angeles.

Sunil Kothari, The Statesman, Calcu0a, March 2, 1982.